Dr Donnell Davis June 2021

This report was presented at the June UNAAQ meeting as a preliminary investigation into the changing policies regarding preventative diplomacy, global citizenship, migration, defence mandate, defence industries, federal audits, and transparency in budget allocations. What happened that we have changed our country from welcoming safe haven to a military investment-house for brokering defence technology? This change undermines the fundamentals of the past 60 years, so it is time to redesign our image in an honourable transparent participatory way.

Even before 1948, Australia was prominent in global peace negotiations and the establishment of the United Nations Declaration with our then Prime Minister Herbert Evatt, drafting the protocols for peace and diplomacy to prevent wars. Australian Peacekeeping was evident in 1947 in Indonesia to prevent further conflict, to build sovereign capacity and to establish a safe environment to heal, with the vision of a future where they can develop the potential of their children. It is an honourable thing to emerge with hope from the rubble of incessant wars.

In my lifetime, Australia has enjoyed a proud reputation for welcoming people to our safe haven – the new life. In the 1950s, Europe endured disastrous floods and many Mediterranean families fled an uncertain future to settle in Australia. This was followed by the ‘ten pound poms’ where we saw open arms to new settlers. This was later followed by Prime Ministers Whitlam and Fraser pleas for families to open their spare bedrooms to Vietnamese seeking a safer home for their children. In the 1990s, the Indo-Pacific efforts saw peacekeeping through Cambodia Peace Accord (Gareth Evans), and later efforts in Solomon Islands and Bougainville. At those times international relations, overseas development and aid programs were more active and transparent.

This continued and evolved with the Millennium Development Goals shaping our investment into international projects that benefitted both parties. The AusAID ‘Blue Book’ was the transparent evaluation of how Australian funds were applied to other countries’ peace, prosperity, and participation. A simple matrix was available for all Australians to interrogate and gauge the impact of each Australian dollar invested. All funds were exponentially beneficial for all countries, except our investment in our nearest neighbour Papua New Guinea. The only major visible improvement in our investment into PNG directly by government was in maternal and child mortality; while other indicators were stagnant. So overall, almost every dollar made a positive difference.

In more recent times, business migration peaked and international students catapulted new formulae for universities. Furthermore, young people saw an Australian working holiday as a rite of passage. However, Covid meant big changes, so we cannot compare apples and oranges.

Today, Australia has become “mean” in its attitude towards migration, refugees, international aid, and investment in non-defence technology development. It has become even meaner in its treatment of home-grown charities and NGOs dedicated to philanthropy or any of the humanitarian or environmental or the enabling Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Long established State- approved collection systems have been subsumed by ASIC (Securities Commission) and ACNC (Charities Commission). Consequently, only a narrow scope is available for tax deductibility for gifts to philanthropic organisations. International charities don’t attract tax deductibility status.

Australians have always had deep pockets to help those in need, even without deductible receipts. Is the government taking advantage of our community’s collective compassion for others?

At an international level, are we losing our compassion there too? Australia’s overall SDG performance has crashed from 7th best in the world to 37th (Monash: 2020) in 4 short years, despite adults in Australia being the richest in the world. (https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/one-in-10-australian-adults- are-millionaires-says-report-20210622-p5833t . These are the big picture audits.

The other scoped audits include the investigative interpretations of the federal budget in June 2021. Many commentators give industry perspectives but the most articulate might be this one. NFAW has a team of professionals across disciplines and states, authoring background papers to contribute to a holistic approach to determining the likely impacts of the federal budget. This is now undertaken voluntarily; although it was funded by government until 2014, when transparency was seen as a useful management tool. (NFAW: 24 May 2021)

Extract: inequalities embedded in Australia’s labour market, tax system and transfer systems were never going to be resolved in a single budget. However, the budget missed the opportunities to address long-standing issues of inter-generational inequity and poverty, act on climate change and take a more transformative approach to social infrastructure investments post COVID, such as social housing… underpinning systemic issues weren’t dealt with… NFAW’s concern is that some of the initiatives that received short term funding may be subject to “budget repair” once the government moves away from stimulatory fiscal policy. The result is lost opportunities to invest in real structural solutions that would have led to a greater boost in female employment, addressed the gender pay gap and created real productivity gains through higher wages in the female dominated care industries workforce.

I wish to focus on international investments discussed with Alice Ridge IWDA on 11 June 2021. The graph below shows decline in international aid (ODA) but reported in absolute dollars in the budget.

- Australia’s investment in international aid has been the lowest since 1954 (Langmore),

- Australia ranked 22ndout of 29OECD

- Australia’s investment in defence forces is 10 times that of Aid budget.

- Australia’s investment in defence industries is often hidden and dispersed through innovation budgets and state budgets not just the federal budget, so not properly reported (i.e. Queensland is establishing a CRC for Defence with $11.5m of $65million from the state budget – June 2021)

- The highest impacts for returns on investment are well-planned

- Priority is placed on our Pacific neighbours and Asian development. This is appropriate and funding is more transparent there than here internally.

- The Canadian Model for Foreign Policy Investment has principles that embed 50/50 planet (since 2008) ensuring greater participation for all players in the economy

https://nfaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/International-Development.pdf

Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific https://www.aiffp.gov.au/our- principles

According to independent reviews, the Defence Force comprises Airforce, Navy and Army with their supporting systems. The role of Defence is “to protect and defend” Australia from threats to our safety: through defensive and peacetime services. https://www.defencejobs.gov.au/about-the- adf/purpose-and-work. Throughout Asia, their military regimes have animal traits – dragon, snake, poison shrimp (Singapore) – but our Australian animal for military principles is one of the Echidna. It does not show its prickles until it is threatened – so it is supposed to be defensive and protective.

The Lowy Institute: Roggeveen describes (Defence Strategic Update White Paper draft) as: “Echidnas are cute and benign, a threat to none except ants. But they can hurt you if you get too close. In other words, while echidnas aren’t equipped to seek out and destroy enemies, they can impose unacceptable costs on a predator should it try to attack.

Let’s look at the smaller scope audits by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), where cost overruns are so significant that whole other portfolios could be funded instead. https://www.anao.gov.au/work-program/portfolio/defence. Our current Minister for Justice and Attorney General for Australia wished to suppress some of these reports, so this became a headline about transparency in itself. (ABC: Australian Parliament 24 May 2021) One of the outcomes of the 2021-22 budget was that the ANAO operational budget was reduced resulting in less audit capacity.

So how can we interpret defence and military innovation budgets now? Is it opaque on purpose? Is it dispersed on purpose? Is it that we are too complacent to ask for more information? Is it that Minister for super agency Peter Dutton determined much of the information to be ‘of national security’ and not open to general scrutiny? We need greater transparency.

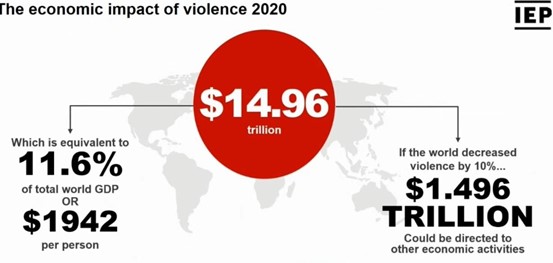

The following images are from the Global Peace Index Report 2021, as at April 2021. The first articulates the cost of violence across the world, and the second demonstrates exacerbation of the impact of Covid inequities leading to violence.

In 1915 there was much scrutiny by ordinary Australians of the war budget. The Women’s Peace Army was a force to be reckoned with and sought finer detail on all monetary arrangements before agreeing and publishing a federal defence budget. (https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/negotiating-the-end-of-war-leading-peace-women- queensland-1909-19.) They were immortalised in the ‘Dames and Daredevils for Democracy’ arts performance.

Several times during my lifetime, there has been public outrage about decisions for defence deployment and other financial investments in offensive style behaviour, evidenced through peace protests by NGOs and individuals. One long poignant concern was banning nuclear weapons, where Australian ICAN coalition for nuclear disarmament was recognised for its efforts with Nobel Peace Prize here in 2017 ( https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/tpnw/). Recently, the United Nations ratified the treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons.

One of my own family members works for a multinational company designing and developing innovative defence paraphernalia in Australia. This is big business. So I need to appreciate the opportunities for scientific and engineering advancement while being concerned about the ethics of the end-use.

In contrast to exponential activity in war-toys, investment in preventative diplomacy has been ‘Threadbare’ according to Professor John Langmore and Dr Tania Miletic. Security Through Sustainable Peace: Australian International Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding, emphasises the need for Australia to strengthen diplomacy and includes recommendations for enhancing its role in supporting peace and security in the Indo-Pacific region.

https://arts.unimelb.edu.au/ data/assets/pdf_file/0004/3495721/Security-Through-Sustainable- Peace-Report.pdf

Extracts: So there is a question about whether there are feasible ways in which Australia could contribute more effectively to achieving sustainable peace. Since 2011 there has been a renewed international upsurge in the number of wars and casualties, and in the extent of human displacement and physical destruction. This led UN Secretary-General António Guterres to advocate making conflict prevention central to international policy and to urge Member States to prioritise conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts within their foreign policies.

Is that possible for Australia? We clearly have the capacity to recognise that peace is preferable to war, and also to choose to consciously and honourably adopt policies which would contribute to conflict prevention and peacebuilding. Such action is vital to Australian safety, security and the common good, and requires political commitment to conflict prevention and peacebuilding. If Australia wants to strengthen sustainable credibility for peaceful and just foreign policy, it is important to ensure that domestic policy provides a consistent basis for a humane and equitable international reputation and legitimacy in assisting overseas communities in conflict prevention and peacebuilding. This includes efforts to enhance social cohesion, achieve humane approaches to border security and continuing national reconciliation efforts.

The Minister for Foreign Affairs has principal political responsibility for articulating, planning and implementing international peace processes and in leading departmental attention to them…. Yet the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has been starved of funds…. As Australia’s experience demonstrates, interventions in conflict and instability must prioritise diplomatic engagement and seek political solutions. This learning stands in contradiction to increasing trends of militarisation and securitisation.

In 2021, the Peace Centre was launched in Melbourne University. This is an important step to making preventative diplomacy a reality in Australia. Previously, our young professionals were getting dedicated training overseas, and we were losing that brains trust (because they took international placements leaving a local vacuum in succession planning).

Geraldine Doogue seeks understanding of diplomacy and why it matters. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-15/what-modern-diplomacy-really-looks-like/100137320

There are parallels between preventing wars (between humans) and preventing pandemics (nature’s war against humans). During Covid, the traits of successful leaders are under scrutiny. Those demonstrating compassionate leadership apply (1) empathy to find solutions (2) attentive listening 3) risk-averse: rely on evidence (4) resilience through respect. (Pew Research Centre in Harvard Business Review 2020) We need to reward compassionate leadership in all spheres as a desirable maturity of humanity where well-informed culturally-appropriate dialogue is respected in contrast to spoiled-adolescent responses arising from convoluted foreign policy interpreted through an offensive lens. These skills epitomise diplomacy to optimise resilience in adverse and crisis circumstances. So, how can we embed these as fundamental to Australia’s image?

Diplomacy needs to be funded. There are international models for Peace Productivity Dividends (PPD) to have defence profits re-invested into soft infrastructure like, dialogue protocols, diplomacy skills, systems and qualitative techniques for monitoring progress. UNAAQ in concert with the Peacekeepers ceremony 2018, PPD was canvassed with 3 levels of government, based on (1) research of other country models, (2) UNYP documentary on Masculinity and Peace (in response to Masculinity and War promotion at that time), and (3) the realisation that diplomacy was not being encouraged nor educated nor funded in Australia. Other countries and alliances with Peace Productivity systems included: New Zealand, Canada, Germany, EU, Commonwealth, NEPAD, and Switzerland. In Australia, we seek a productivity dividend from the profits of defence industry profits (taxes) to be allocated toward (1) preventative diplomacy skills development (2) accredited formal education with project placements for experience. In acknowledging that, these skills can be applied in our daily life to design and develop better working relationships, transparent contracts, robust trade agreements, and ongoing programmes of work.

While diplomacy sits under the banner of Peace, these interpersonal skills for maturity in humanity are fundamental to rediscover our culture and to consolidate our identity for Australia as a ‘compassionate leader’ who is prepared to ‘protect and defend’.

So, how do we progress from here?

- Strengthen adherence to the International Rule of

- Embolden a philosophy that encourages Australia to be the Echidna and reflected in our foreign

- Reward compassionate leadership in all spheres as a desirable maturity of humanity where well-informed culturally-appropriate dialogue is More Jaw – Less War.

- More transparency in budgets, where costs overruns are damage-controlled (projects ceased or not started) with forward funds to be diverted to preventative

- Introduce a Peace Productivity Dividend (PPD) as introduced in other countries with varying In Australia, we seek a productivity dividend from the profits of defence industry profits (taxes) to be allocated toward

- preventative diplomacy skills development

- accredited formal education with

- in-country project placements for

Concise PowerPoint available upon request.

Bibliography

ANAO: 2021 Auditor-General Military Cost Over-Runs https://www.anao.gov.au/work-program/portfolio/defence

AUSAid: Blue Book 2008 Evaluating Australian Aid Impacts by country by Millennium Development Goals

Australian Financial Review 2021: Australian Adults richest in the world. (https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/one-in-10-australian- adults-are-millionaires-says-report-20210622-p5833t

Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific: https://www.aiffp.gov.au/our-principles

Australian Women Peace Army: https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/negotiating-the-end-of-war-leading-peace- women-queensland-1909-19.

Doogue Geraldine: 2021 ABC Diplomacy Podcast https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-15/what-modern-diplomacy- really-looks-like/100137320

Institute for Economics and Peace: 2021 Global Peace Index report https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp- content/uploads/2021/06/GPI-2021-web-1.pdf

International Women’s Development Association 2021: Alice Ridge Australian Aid budget 2004 – 2025 (proceedings from Status of Women Network 11 June) citing Canadian Feminist Foreign Policy Framework

Lowy Institute: 2021 Defence Strategic Update White Paper draft

Monash University: 2020 https://www.sdgtransformingaustralia.com/wp-content/uploads/MSDI_TA2020_Summary.pdf

National Foundation for Australian Women: 2021 Gender Responsive Budgeting. https://nfaw.org/policy-papers/gender- lens-on-the-budget/gender-lens-on-the-budget-2021-2022/

Langmore & Miletic: 2021 Preventative Diplomacy Pathway for Australia

About the Author

Dr Donnell Davis, from rural Queensland, gained 25 years diverse experience in government, followed by 16 years working locally and internationally with private sector and charities. She studied and practiced accounting, audit, evaluation, public policy, ethics, sustainable development, urban and regional planning, environmental law, urban design, climate governance, women’s policy and interdisciplinary innovation. She now consults, teaches and is a prolific writer.

Dr Donnell Davis, from rural Queensland, gained 25 years diverse experience in government, followed by 16 years working locally and internationally with private sector and charities. She studied and practiced accounting, audit, evaluation, public policy, ethics, sustainable development, urban and regional planning, environmental law, urban design, climate governance, women’s policy and interdisciplinary innovation. She now consults, teaches and is a prolific writer.