COVID-19 threatens the health and wellbeing of millions of people the world over, through malnutrition, preventable disease, delayed diagnoses and psychological hardship. All these threats co-exist with the threat of the virus itself, and are consequences of economic and social ‘lockdowns’ imposed by governments to curb the spread of COVID-19.

Understanding the intimate link between the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 – Decent Work and Economic Growth – and SDG 3 – Good Health and Wellbeing – will be crucial to mapping a road to recovery for our world, when we eventually emerge from the current health crisis and global recession.

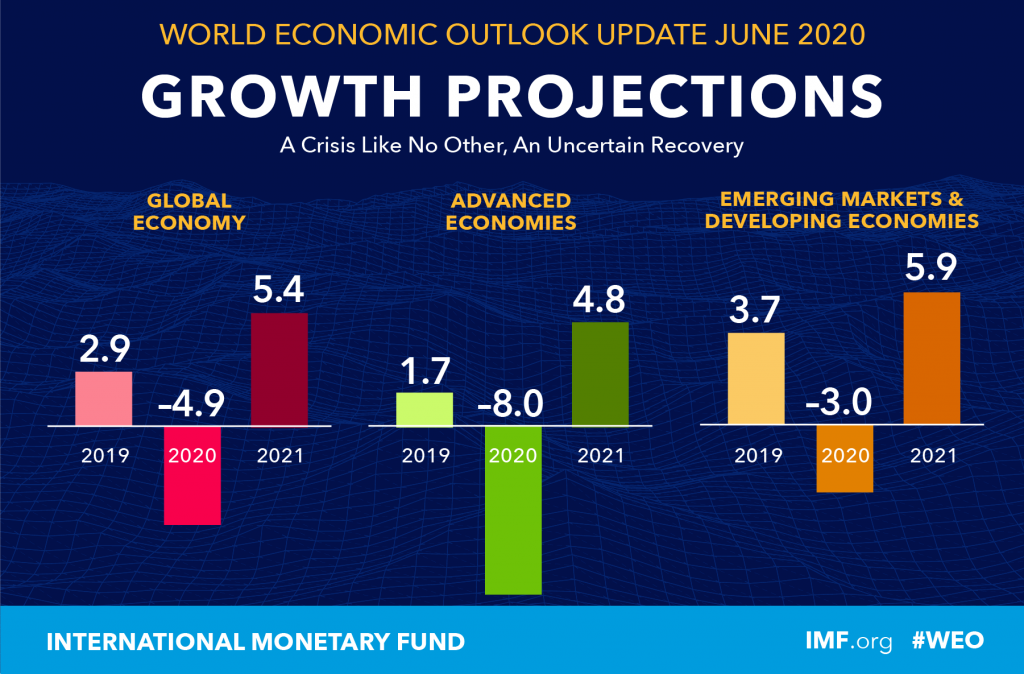

The upheaval created by the pandemic has challenged predominant economic theories, particularly Milton Friedman’sneoliberal ideas about a self-regulating ‘free market’. The current health crisis has created mass unemployment across a range of sectors and countries, in both the developed and developing world. As a result, many countries have intervened in their economies with emergency social security packages, and the IMF reports it has already issued $100 billion USD in loans to over 60 countries to fund these schemes. Projections indicate global economic growth will be -4.9 percent in 2020, and many expect the economic downturn to continue well into 2021 and 2022, depending on when a COVID-19 vaccine is made widely available.

Our world’s rapidly changed economic conditions, coupled with rising concerns for public health, have forced both economists and politicians to call into question what really matters for the health and wellbeing of a society. Global leaders are now wondering: what conditions are truly essential for people to live prosperously?

Coping with COVID-19: the trouble with staying home

A recently published open letter from 265 Australian economists to Prime Minister Scott Morrison advocated for economic recovery to remain secondary to public health as Australia eases its lockdowns. “It is wishful thinking to believe we face a choice between a buoyant economy without social distancing and a deep recession with social distancing,” the letter states, calling for leaders not to lift restrictions prematurely in order to salvage the economy.

Nowhere have the consequences of a hasty return to ‘normal’ been more evident than in Victoria, where a shift from Stage 3 to Stage 2 restrictions in May 2020 was followed by the imposition of much stricter Stage 4 restrictions just over two months later. This measure was taken in response to a worrying surge in new COVID-19 cases, deemed Victoria’s ‘second wave’ of the virus.

Thus far, Stage 4 restrictions appear to have been successful in reducing the spread of the virus, but mounting concerns about the side-effects of staying home have many worried that the restrictions may cost as many lives as they save. For example, a 30% drop in new cancer diagnoses since March 2020 has oncology professionals anxious that many people are postponing visits to their GP, and as a result will have more advanced cancers when they are eventually diagnosed. Mental health is another prominent concern, to which the Federal Government recently responded with a $20 million funding boost for mental health and suicide prevention programs.

The negative health and wellbeing consequences of lockdowns are even more concerning in the developing world. The World Bank estimates that in low-income countries, as few as 12% of jobs can be worked from home and employment in the informal sector is common, meaning many currently unemployed people are not entitled to income protection. As a result, the World Bank estimates between 49-400 million people will be pushed into extreme poverty during the pandemic, depending on how long it continues. Increased poverty is expected to have a range of dire consequences, including the doubling of acute hunger before the end of 2020.

Many epidemiologists are now advocating for more moderate lockdowns as a result of these health threats, particularly in the developing world. Prior Ebola epidemics are suggested as a model to use, which focus on physical distancing, masks and hygiene, without creating mass unemployment.

The link between good health and decent work is undeniable: for many, being unable to work means encountering severe mental and physical health risks. As such, it is imperative that world leaders confront the challenge of empowering people to work and remain healthy simultaneously as we establish our ‘new normal.’

At a time like this, does national interests trump multilateralism?

A concerning turn in world politics in 2020 has been the rise of populist leaders, whose rhetoric and policies focus exclusively on national interest. Their catch cry is that helping others – the developing world; neighbouring countries – can only be done at the expense of a country’s own citizens. President Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the World Health Organization (WHO) is perhaps the most startling recent example of this. This decision will deprive the WHO of important financial backing, at a time when funding is crucial to help low- and middle-income countries navigate the COVID-19 crisis.

President Trump is not alone in his abandonment of multilateralism, and Australia’s own Prime Minister was quoted in April this year telling international students and temporary visa holders in Australia it was “time to go home” so Australia could focus on caring for its citizens. Representatives from the International Education Association of Australia warned that the Prime Minister’s comments had harmed Australia’s international reputation as a world leader in education, and harmed important relationships with allies and trading partners.

At a time when many developed countries are turning inwards and abandoning foreign diplomacy, how can the multilateral cooperation that created the United Nations and cemented commitments to the UN Sustainable Development Goals expect to recover? UN Secretary-General Atónio Guterres has spoken openly about the need for countries to come together in order to recover from the pandemic at a meeting about financing sustainable development in April this year.

“A virus…knows no borders: all countries are affected. The fight against this global pandemic, which is taking so many lives and challenging our societies, is a stark reminder that the world needs more, not less multilateral cooperation and global solidarity.”

Working collaboratively towards a healthy and prosperous ‘new normal’

In the pursuit of a ‘new normal’, leaders must cautiously balance stimulating economic growth and curbing the spread of COVID-19, and be aware of the complex social and economic conditions that create a prosperous society. Economic theories and policymaking strategies have been confronted with unprecedented challenges in 2020, but knowledge and resource sharing can assist in the pursuit of strategies for global recovery. This includes a COVID-19 vaccine itself, which Guterres has said must be considered a “global public good.”

The UN can play a critical role in providing stewardship for global conversations about how to transition the world to its ‘new normal’, but it is only through the willingness of leaders to work in solidarity, to heed the advice of experts, and to listen to the needs of ordinary people that robust and enduring solutions can be achieved.

Written by: Maeve Martyn, Marketing and Communications Manager, UNAAV YP Network