Although we are currently facing a public health crisis, COVID-19 has also caused a surge in intimate partner violence (IPV), negatively affecting our world’s pursuit of SDG #5: Gender Equality.

While stage three restrictions have been reinforced in order to control the pandemic’s spread in Metropolitan Melbourne, stay-at-home mandates have also left many women and girls trapped at home with their abusers.

Women have been at the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic, making up 75% of health professionals in Australia and 67% of the global health workforce. Women and girls also take on the lion’s share of unpaid work in our societies, accounting for 64% of unpaid work in Australia and 76% globally. Gendered economic and social inequalities are maintained as women take on the majority of caring responsibilities, leaving them less time for education, paid work, and professional development.

The World Health Organisation defines Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) as “behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviours.” This definition covers violence by both current and former spouses and partners.

In Australia, statistics on violence against women were daunting even before the pandemic began. One in three women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence, and one in four have experienced violence by a current or former intimate partner.

Studies of epidemics and natural disasters indicate that humanitarian crises result in an augmentation of gender-based violence. Like natural disasters, COVID-19 has caused unanticipated shifts in our day-to-day routines, including closures of schools and community centres. The pandemic has also led to a decrease in the availability of many services and resources, and a widespread increase in people’s experiences of mild and acute stress.

As a result, the risk factors for family violence have been amplified during COVID-19. These risk factors include: unemployment; insufficient social support; limited financial resources; desire for control; and alcohol abuse. Sheltering-in-place has given more power to abusers in relationships in which IPV exists, as victims’ support networks have been cut off, making it even harder for them to escape.

“Home can be a place where dynamics of power can be distorted and subverted by those who abuse, often without scrutiny from anyone ‘outside’ the couple, or the family unit”

Since stay-at-home restrictions have commenced, reports of domestic violence have risen around the world. In France, there has been a 30% increase; Brazil estimates a 40-50% increase; and China reports that domestic violence has tripled in 2020, as compared with 2019.

In Australia, Google searches for help with domestic violence have risen 75% since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March, which is the highest frequency recorded over the past five years.

Calls to emergency support lines for domestic violence victims have also escalated across the globe since restrictions began. For instance, rapid increases were recorded in the UK (25%), Spain (20%), Argentina (25%), Cyprus (30%), and Singapore (33%). In Canada, the Vancouver Battered Women’s Support Services has received triple the amount of calls they ordinarily would. In India, complaints of domestic violence received by the National Commission for Women have doubled.

Executive Director of UN Women, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, has labelled this surge of domestic violence, the Shadow Pandemic.

UN Secretary-General, António Guterres has urged governments to set up emergency warning systems for those facing family violence, to prioritize support through increasing investment in online services and civil society organisations, and to declare shelters as essential services:

Some governments, including Australia, have heeded Guterres’s advice. Australia has allocated $150 million towards its National Plan to support victims of domestic violence which will fund counselling support, 1800RESPECT, Mensline Australia, Trafficked People Program, and other support services.

The French government recently announced they will pay for 20,000 hotel rooms for victims, open pop-up counselling centres, and allocate one million euros in funding for anti-domestic abuse organisations. The Canarian Institute for Equality in Spain started an initiative in which victims are told to use a codeword ‘mascarilla-19’ (‘mask 19’) in pharmacies to seek help. This protocol has been enacted in several countries such as Australia, Italy, Germany, France, Norway, UK, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, Uganda, and Cape Verde.

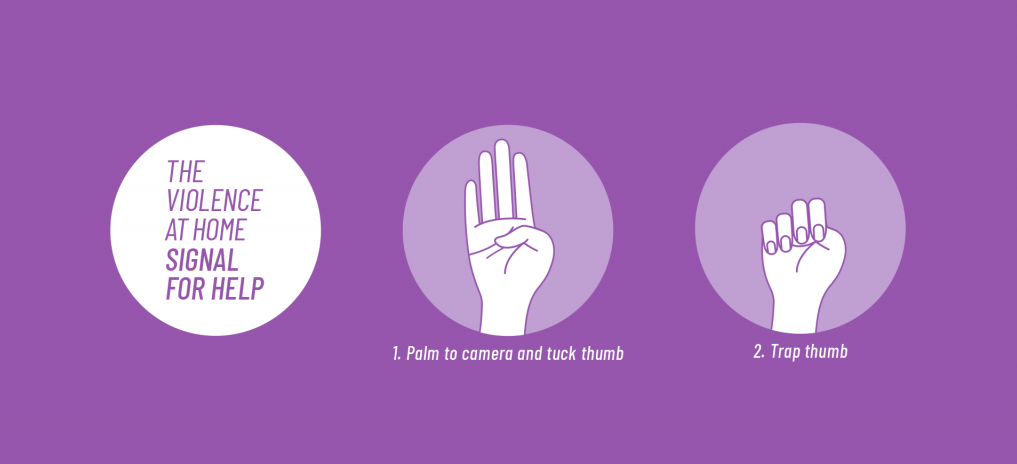

Canada has allocated $40 million to women’s shelters and sexual assault centres, as well as $10 million to Indigenous Services Canada’s shelters. The Canadian Women’s Foundation launched the ‘Signal for Help Campaign’, where victims can use a hand gesture to inaudibly show they need help via webcams, as pictured above. This system has now been used by organisations around the world.

These strategies must continue when lockdown restrictions ease, as they will be critical in implementing gender equality as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic.

For more information, visit Coronavirus (COVID-19) and family violence.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault, domestic or family violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au.

In an emergency, call 000.

Written by: Victoria Yutronich, Communications Coordinator, UNAAV YP Network

Edited by: Maeve Martyn, Marketing and Communications Manager, UNAAV YP Network